Do you want to develop innovations that meet the needs of your target group? Then you should take one central and particularly helpful basic principle to heart.

It was a few years ago when we investigated the potential of a music streaming provider in Germany. At that time, this service was already popular, especially in Scandinavia, but not yet established in this country. Participants in group discussions were very skeptical. Paying monthly for access to your music without owning it is like going to a prostitute whorehouse. After all, you love your music and are connected to it through a shared history.

If we had taken the consumers’ wishes at face value back then, we would have had to urgently advise our client against a launch in Germany. But we didn’t. Instead, we took a closer look at the needs behind the wishes. Sure, there’s the desire for an audible biography, which for some time now has been tied to one’s own “record collection” — but there’s no real need for music ownership. This seemed to us more like a temporary cultural phenomenon, triggered by the invention of the vinyl record and already in the process of slowly disappearing again with the CD and MP3 players. In addition, there are still needs for mood modulation, for a portable emotional pharmacy, for inspiration and a lot more. The recommendation was therefore: Do it!

In innovation processes, too, queried desires are not a reliable indicator of the potential of new offerings. Consumers find it hard to imagine them, they develop initial resistance, who wants to change their habits? They behave like the people in Kaiser Wilhelm’s time, who — as is rumored — wanted faster horses instead of cars.

This is where a very important, central and particularly helpful basic principle of innovation development comes into play: abstraction. Away from the concrete wishes. Instead, uncover the fundamental need behind it and develop the innovation precisely for this purpose. Only then does the view become free for new or truly disruptive innovations.

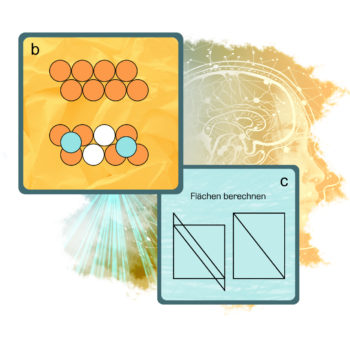

This principle is also known from the TRIZ invention method. It is rather unknown in marketing circles, because it refers to technical inventions, but uses the same basic principle. It was developed in the 1950s in what was then the Soviet Union. In TRIZ, a technical problem is first abstracted at a higher level. Then an abstract solution is found and brought back down to a concrete solution. An example: Instead of the question “How do I improve a lawn mower?”, the question is: “How do I make the lawn short? The concrete solution can then also be a genetically modified lawn that stops growing at 5 cm.

Transferred to innovations for consumers, the abstract question is of course about the actual needs. In the example of music streaming, for example, it was the need for permanently available mood modulation. For the nostalgics, vinyl — for this target group, vinyl has even taken off again — but for everyone else, please, music streaming. Cars instead of horses, so to speak.

Our expert tip: Be careful with innovation processes and methods that claim to be consumer-centric, but are based directly on their wishes and do not take this step towards abstraction (without wanting to mention specific methods, such as Design Thinking, by name). Your ideas will be more disruptive and user-oriented if you approach them with a system.